Cement hides in plain sight—it’s used to build everything from roads and buildings to dams and basement floors. But there’s a climate threat lurking in those ubiquitous gray slabs. Cement production accounts for more than 7% of global carbon dioxide emissions—more than sectors like aviation, shipping, or landfills.

Humans have been making cement, in one form or another, for thousands of years. Ancient Romans used volcanic ash, crushed lime, and seawater to build the aqueducts and iconic structures like the Pantheon. The modern version of hydraulic cement—the sort that hardens when mixed with water and allowed to dry—dates back to the early 19th century. Derived from widely available materials, it’s cheap and easy to make. Today, cement is one of the most-used materials on the planet, with about 4 billion metric tons produced annually.

Industrial-scale cement is a multifaceted climate conundrum. Making it is energy intensive: the inside of a traditional cement kiln is hotter than lava in an erupting volcano. Reaching those temperatures typically requires burning fossil fuels like coal. There’s also a specific set of chemical reactions needed to turn crushed-up minerals into cement—and those reactions release carbon dioxide, the most common greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.

One solution to this climate catastrophe might be coursing through the pipes at Sublime Systems. Founded by two MIT battery scientists, the startup is developing an entirely new way to make cement. Instead of heating crushed-up rocks in lava-hot kilns, Sublime’s technology zaps them in water with electricity, kicking off chemical reactions that form the main ingredients in its cement.

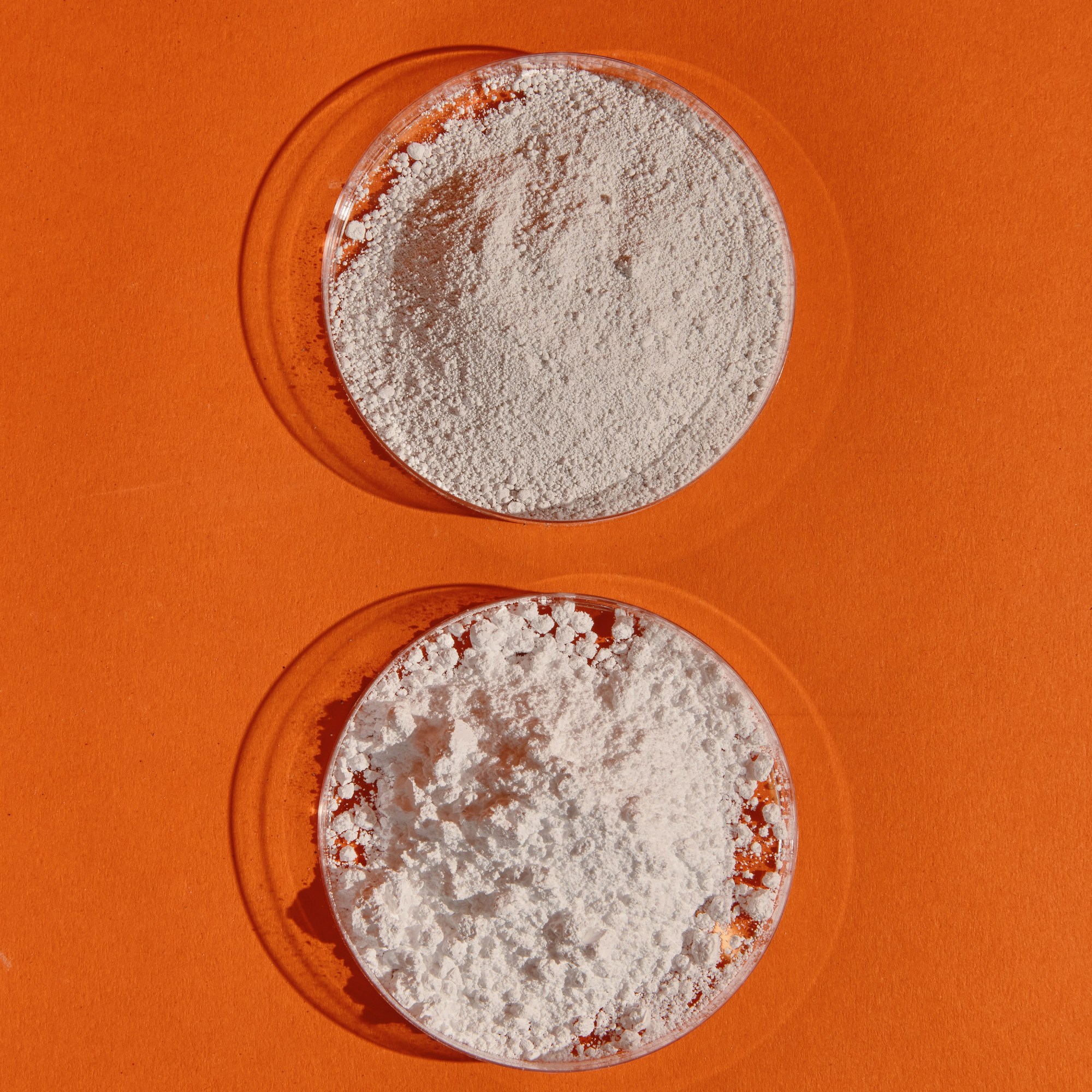

Sublime silicates (top dish) and lime (bottom dish) are the two main reactive components for making Sublime Cement.

Over the course of the past several years, the startup has gone from making batches of cement that could fit in the palm of your hand to starting up a pilot facility that can produce around 100 tons each year. While it’s still tiny compared with traditional cement plants, which can churn out a million tons or more annually, the pilot line represents the first crucial step to proving that electrochemistry can stand up to the challenge of producing one of the world’s most important building materials.

By the end of the decade, Sublime plans to have a full-scale manufacturing facility up and running that’s capable of producing a million tons of material each year. But traditional large-scale cement plants can cost over a billion dollars to build and outfit. Competing with established industry players will require Sublime to scale fast while raising the additional funding it will need to support that growth. The end of 0% interest rates makes such a task increasingly difficult for any business, but especially for one producing a commodity like cement. And in a high-stakes, low-margin industry like construction, Sublime will need to persuade builders to use its material in the first place.